It has been expanding ever since.

The newly opened Dabbahu fissure on 16 October 2005, with people for scale. Photo: Anthony Philpotts via Julius Badayos

Africa is undergoing a dramatic geological transformation that will eventually split the continent into two and create a new ocean. This process is happening in the Afar region of Ethiopia, where a giant crack in the earth’s crust is widening and deepening, exposing the hot magma beneath.

The crack, known as the East African Rift, is a result of three tectonic plates pulling away from each other. The Nubian plate and the Somali plate are moving west and east respectively, while the Arabian plate is moving north. As these plates diverge, they create gaps that are filled by molten rock from the mantle, forming new crust and volcanoes.

Scientists say that Africa is set to split into two, creating a new ocean.

The East African Rift is not a new phenomenon. It has been active for millions of years, and it is responsible for shaping some of the most iconic landscapes of Africa, such as the Great Rift Valley, Lake Victoria, Mount Kilimanjaro, and the Red Sea.

However, what makes the Afar region, and the Afar Depression in particular, unique is that it is one of the few places on Earth where the rifting process can be observed on land. Most of the time, continental rifting occurs underwater, hidden from view.

The Dabbahu-Manda-Hararo rift, part of the East African rift, with the Dabbahu volcano in the background. Photo: DavidMPyle

The most dramatic evidence of the rifting in Afar came in 2005, when a massive eruption at the Dabbahu volcano triggered a series of earthquakes that opened up a 35-mile (60 km) and 26-feet (8 meters) wide fissure in just ten days. The ground between the fissure dropped by several meters, creating a depression that will eventually become a new sea floor. This event was described by scientists as “truly incredible” and “the birth of a new ocean”.

Using the seismic data from the 2005 eruption, in 2009 researchers reconstructed the event to demonstrate that the rift rapidly split its entire 35-mile span within a matter of days, initiated by the eruption of the Dabbahu volcano, which is situated at the northern end of the rift. Subsequently, magma surged upward through the central rift region, initiating the gradual separation of the rift in both directions.

Aerial view of the Dabbahu fissure. Photo: Asfawossen Asrat/Smithsonian

“We know that seafloor ridges are created by a similar intrusion of magma into a rift, but we never knew that a huge length of the ridge could break open at once like this,” said lead researcher Cindy Ebinger, professor of earth and environmental sciences at the University of Rochester, back then.

Since then, the rifting has continued at a slower pace, but with occasional bursts of activity. In 2009, another volcanic eruption created a 14 km long crack that spewed lava and ash. In 2017, heavy rains caused a landslide that exposed a 15 meter deep crevice. In 2019, satellite images revealed that the rift had widened by 4 cm in just six months.

“We can see that oceanic crust is starting to form, because it’s distinctly different from continental crust in its composition and density,” said Christopher Moore, a Ph.D. doctoral student at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom, who has been using satellite radar technology to observe volcanic movements in East Africa, which are linked to the ongoing process of the continent’s separation.

The central section of 35-mile-long rift zone that opened south of the Dabbahu volcano. Photo: Julie Rowland, University of Auckland

The rifting in Afar is not only fascinating for geologists, but also for biologists, archaeologists, and anthropologists. The region is home to diverse and endemic flora and fauna, some of which are adapted to the harsh and hot environment. The region is also rich in fossils and artifacts that shed light on the origins and evolution of humans and their ancestors.

The rifting may also have implications for the climate, biodiversity, and socio-economic development of Africa and beyond.

Newly exposed fault scarp formed from dike-induced faulting during the September 2005 rifting event in the Dabbahu segment in the Afar rift. Photo credit: Derek Keir, National Oceanography Centre Southampton, University of Southampton

But how long the process of forming a new ocean will take place? When will it exactly happen?

Well, we don’t know for sure, but according to the current mainstream hypothesis, the Red Sea will eventually flow into the emerging sea in approximately a million years. This newfound ocean would establish a connection between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, an arm of the Arabian Sea between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Somalia in eastern Africa.

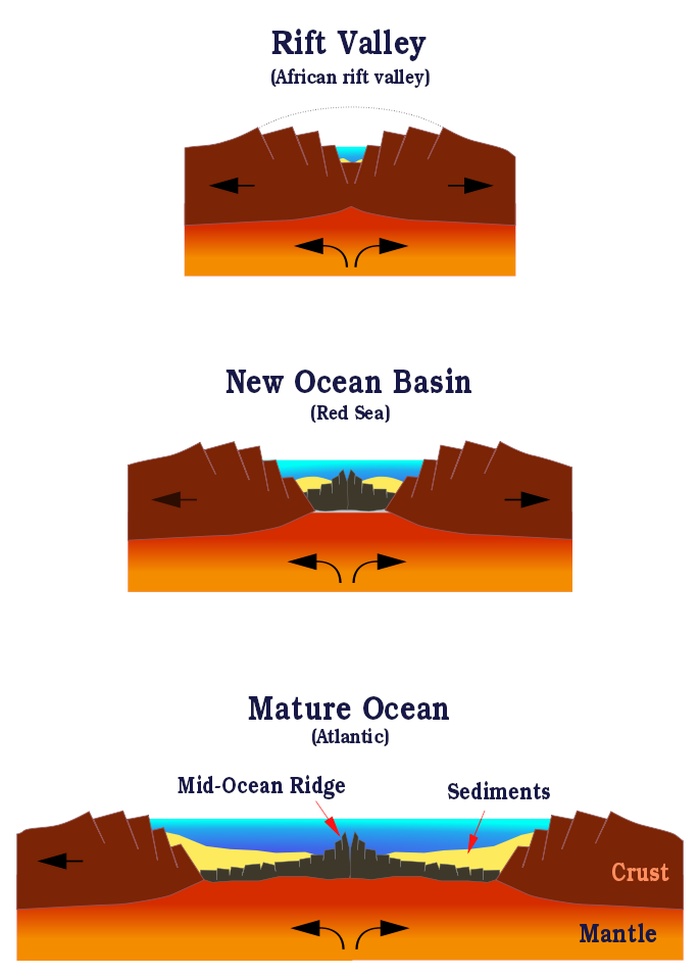

The birth of an ocean: within the framework of plate tectonics, the creation of an ocean commences with a process of crustal rifting caused by mantle convection. A notable instance of this phenomenon is the African Rift Valley. In the subsequent phase, the rift valley widens until it allows seawater to infiltrate, exemplified by the formation of the Red Sea. The spreading process persists, gradually expanding the ocean and ultimately leading to the development of a fully mature ocean, as seen in the case of the Atlantic Ocean. Graphics: Hannes Grobe, Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research

The rifting in Afar is a rare opportunity to witness one of the most fundamental processes that shape our planet: plate tectonics. It is also a reminder of how dynamic and complex our Earth is, and how much we still have to learn about it.